Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR) is a frequently applied method for alveolar bone reconstruction and addressing peri-implant deficiencies. It utilizes bone grafts and membranes

to stimulate new bone growth in areas lacking sufficient volume, proving a valuable technique in modern dentistry.

Historical Context of GBR

The foundations of Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR) trace back to the 1950s, with early explorations into guided tissue regeneration primarily focused on periodontal defects. Pioneering work by Dr. Per-Ingvar Brånemark in the 1960s, concerning osseointegration and dental implants, significantly influenced the field.

Initially, techniques centered around utilizing barrier membranes to prevent soft tissue ingrowth into bony defects, allowing bone cells to populate the space. Over time, the understanding of bone biology and biomaterials evolved, leading to the incorporation of bone graft materials to enhance bone formation. The 1980s and 90s witnessed the refinement of GBR techniques, becoming a standard approach for alveolar ridge augmentation and peri-implant bone reconstruction, continually improving patient outcomes.

The Core Principle: Exclusion of Soft Tissues

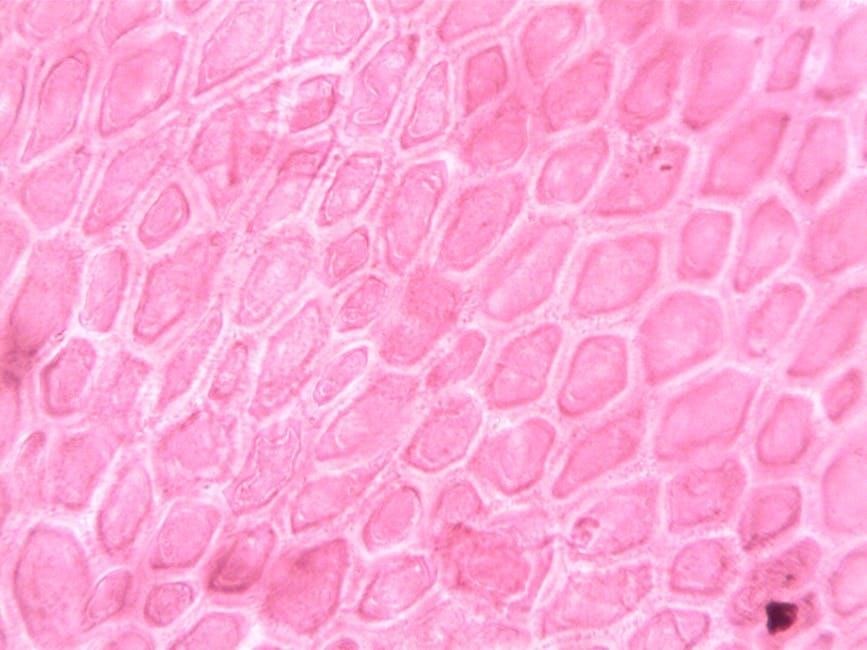

The fundamental principle underpinning Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR) revolves around creating a protected space, free from the competitive influence of soft tissues. This is achieved through the strategic placement of a barrier membrane, preventing fibroblasts and epithelial cells from migrating into the defect.

This exclusion allows osteogenic cells – bone-forming cells – to migrate, proliferate, and differentiate within the confined space, ultimately leading to predictable bone formation. Without this barrier, soft tissue ingress would hinder bone regeneration, compromising the success of the procedure. The membrane acts as a biological scaffold, directing the healing process towards bone reconstruction.

Key Components of Guided Bone Regeneration

GBR relies on two essential components: bone graft materials, providing the building blocks for new bone, and barrier membranes, crucial for tissue exclusion and guiding regeneration.

Bone Graft Materials

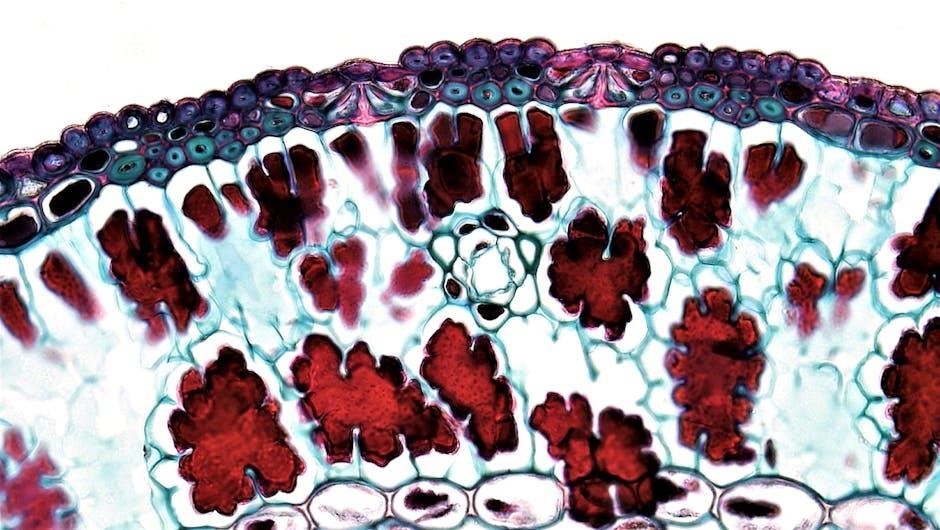

Bone graft materials are fundamental to successful Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR), providing the necessary scaffold for new bone formation. These materials possess varying properties – osteogenic, osteoinductive, or osteoconductive – influencing their ability to directly form bone, stimulate bone growth, or simply support bone cell attachment and proliferation.

The selection of a suitable graft material is critical and depends on the defect characteristics and clinical goals. Several categories exist, including allografts (derived from human donors), xenografts (sourced from other species, commonly bovine), and synthetic bone substitutes. Each option presents unique advantages and disadvantages regarding biocompatibility, osteoconductivity, and potential for immune response, demanding careful consideration by the clinician.

Allografts in GBR

Allografts, derived from human donors, represent a biologically active option for Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR). They contain osteogenic cells, growth factors, and bone matrix proteins, potentially accelerating bone formation. However, allografts carry a theoretical risk of disease transmission, though rigorous screening and processing protocols significantly minimize this concern.

Despite this, allografts often exhibit excellent osteoconductivity and integration with the recipient site. Their biological properties can be particularly beneficial in large defects or situations requiring rapid bone healing. Careful handling and adherence to established guidelines are crucial when utilizing allografts to ensure patient safety and optimal clinical outcomes.

Xenografts: A Common Choice

Xenografts, sourced from animal tissues – typically bovine – are a widely utilized bone graft material in Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR) due to their availability and cost-effectiveness. These materials possess excellent osteoconductive properties, providing a scaffold for new bone formation. While lacking viable osteogenic cells, xenografts stimulate the patient’s own bone cells to populate the graft site.

Processing methods, such as demineralization and sterilization, are crucial to eliminate immunogenicity and ensure biocompatibility. Xenografts demonstrate predictable results and are considered a safe alternative to autografts and allografts in many clinical scenarios, making them a popular choice for alveolar ridge augmentation.

Synthetic Bone Substitutes

Synthetic bone substitutes represent a continually evolving category within Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR), offering predictable and customizable options. These materials, often composed of calcium phosphates like hydroxyapatite or tricalcium phosphate, mimic the mineral composition of natural bone, promoting osteoblast adhesion and bone matrix deposition. They eliminate concerns regarding disease transmission or immunological reactions associated with allografts or xenografts.

Variations include bioactive ceramics and polymers, sometimes combined with growth factors to enhance osteoinduction. While generally osteoconductive, some synthetic substitutes lack inherent osteoinductive potential, requiring augmentation with other materials for optimal results. Their ease of handling and consistent properties make them increasingly attractive.

Barrier Membranes

Barrier membranes are a cornerstone of Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR), playing a crucial role in excluding soft tissue from the defect site, allowing bone cells to populate and regenerate. These membranes create a protected space for bone graft materials, preventing competition from fibroblasts and epithelial cells. They act as a temporary scaffold, guiding the regenerative process.

Membrane selection is paramount, considering factors like biocompatibility, barrier function, and space-making ability. Both resorbable and non-resorbable options exist, each with advantages and disadvantages depending on the clinical scenario. Proper membrane adaptation and stability are essential for successful GBR outcomes, ensuring complete bone coverage.

Types of Membranes: Resorbable vs. Non-Resorbable

Resorbable membranes, often collagen-based, offer the advantage of eliminating a second-stage surgery for removal, simplifying the procedure for both surgeon and patient. They degrade over time, aligning with the bone regeneration process. However, they may offer less long-term stability, potentially leading to early membrane exposure.

Non-resorbable membranes, typically made of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE), provide a robust barrier and maintain space for a prolonged period. They require a second surgical intervention for removal, but offer greater predictability in maintaining the protected space. The choice depends on defect size, stability needs, and surgeon preference.

Membrane Selection Criteria

Membrane selection in Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR) hinges on several critical factors. Defect morphology – whether it’s a small, contained defect or a larger, more complex one – dictates the required barrier function and stability. Tissue biotype, including soft tissue thickness, influences the risk of membrane exposure.

Barrier membrane characteristics, like porosity and hydrophobicity, impact cell integration and vascularization. Resorbable versus non-resorbable options are chosen based on healing time and surgical complexity. Finally, clinical experience and cost-effectiveness play a role in the ultimate decision, ensuring optimal outcomes for each patient’s unique needs.

Surgical Techniques in Guided Bone Regeneration

Surgical techniques for GBR involve direct or indirect grafting approaches, precise membrane placement, and meticulous stabilization of both the graft and the barrier membrane.

Grafting Approaches: Direct vs. Indirect

Direct grafting in Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR) involves placing the bone graft material directly into the defect site, often alongside the barrier membrane. This approach is typically favored for smaller, contained defects where primary closure can be readily achieved, ensuring close contact between the graft and the bone. It aims for predictable bone formation with minimal collapse.

Indirect grafting, conversely, utilizes a space-making approach. The membrane is first positioned, creating a confined space, and then the graft material is inserted. This technique is beneficial for larger defects or situations where primary closure is challenging. The membrane prevents soft tissue ingrowth, allowing bone to grow into the space, promoting volume gain and stability. The choice between these methods depends on defect morphology and clinical goals.

Membrane Placement Techniques

Membrane placement is a critical step in Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR). Techniques vary based on defect size and graft type. One common method involves carefully adapting the membrane to the prepared bone surface, ensuring complete coverage of the defect to exclude soft tissue. Precise adaptation minimizes space, promoting graft stability.

Another technique utilizes a tenting approach, particularly for larger defects. The membrane is secured beyond the defect margins, creating a space for graft material. Proper tension is crucial – too tight can compromise blood supply, while too loose risks membrane exposure. Secure fixation with sutures or tacks is essential for maintaining the space and preventing early contamination, ultimately influencing GBR success.

Stabilization of the Graft and Membrane

Effective stabilization of both the bone graft and the barrier membrane is paramount for successful Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR). Initial stability is often achieved through meticulous adaptation of the membrane to the bone defect, ensuring close contact and minimizing potential space for soft tissue ingress.

Suturing techniques play a vital role, securing the membrane firmly to the surrounding periosteum and, in some cases, to the adjacent tooth or implant. Resorbable sutures are frequently used to avoid a second surgery for removal. Additionally, fixation devices like tacks or pins may be employed, particularly in larger defects, to provide enhanced mechanical stability and maintain the desired graft volume throughout the healing phase.

Applications of Guided Bone Regeneration

GBR’s versatility allows for treatment of peri-implant bone defects, alveolar ridge augmentation, and sinus lift procedures, effectively reconstructing bone for dental implant placement.

Peri-Implant Bone Deficiencies

Addressing bone loss around dental implants is a primary application of Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR). Often, insufficient bone volume exists at the implant site, or develops post-implantation, compromising long-term stability and aesthetics. GBR effectively reconstructs this lost bone, creating a solid foundation for the implant fixture.

The technique involves carefully placing bone graft material – allografts, xenografts, or synthetic substitutes – into the defect area. A barrier membrane is then positioned to shield the graft, preventing soft tissue ingrowth and allowing bone cells to populate the space. This controlled environment encourages predictable bone formation, restoring the necessary bone height and width to support the implant and surrounding tissues, ultimately enhancing treatment outcomes and patient satisfaction.

Alveolar Ridge Augmentation

Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR) is a widely utilized technique for augmenting deficient alveolar ridges, often following tooth extraction or experiencing bone resorption. This procedure aims to restore bone volume and create an ideal foundation for future restorative treatments, such as dental implants or prosthetics. The process involves meticulous placement of bone graft materials to fill the ridge defect.

Subsequently, a barrier membrane is applied to isolate the graft, preventing soft tissue encroachment and promoting bone regeneration. This controlled environment allows for predictable bone formation, widening and heightening the alveolar ridge. Successful alveolar ridge augmentation with GBR ensures optimal implant placement, improved aesthetics, and enhanced functional rehabilitation for patients with significant bone loss.

Sinus Lift Procedures with GBR

Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR) plays a crucial role in sinus lift procedures, particularly when insufficient bone height exists in the posterior maxilla for implant placement. This technique elevates the sinus membrane, creating space for bone grafting. GBR enhances the predictability and success rate of these procedures by providing a barrier to prevent soft tissue down-growth into the grafted sinus cavity.

Bone graft materials, often combined with resorbable or non-resorbable membranes, are carefully positioned. The membrane shields the graft, allowing osteogenic cells to populate and mature into new bone. This results in increased bone volume, enabling secure and stable dental implant placement in the previously inadequate region, ultimately restoring function and aesthetics.

Factors Influencing GBR Success

GBR success hinges on patient health, surgical precision, and meticulous post-operative care. These elements, working in synergy, optimize bone regeneration and implant stability.

Patient-Related Factors

Numerous patient characteristics significantly impact Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR) outcomes. Systemic conditions like diabetes, osteoporosis, and smoking habits demonstrably compromise bone healing capabilities. A patient’s overall health status, including immune function, plays a crucial role in the regenerative process.

Furthermore, age can influence bone metabolism and the capacity for new bone formation. Patients with a history of bisphosphonate use may experience impaired bone regeneration. Adequate vascular supply to the surgical site is also paramount; compromised circulation hinders graft integration and healing.

Therefore, a thorough medical and dental history, coupled with a comprehensive clinical examination, is essential to identify and address potential patient-related risk factors before initiating GBR treatment.

Surgical Precision and Technique

Achieving predictable GBR outcomes hinges on meticulous surgical execution. Precise flap design and elevation are critical for adequate visualization and access to the defect site. Careful handling of soft tissues minimizes trauma and preserves vascularity, essential for graft nourishment.

Proper graft containment is paramount; the barrier membrane must achieve a complete seal to exclude soft tissue ingrowth and allow bone cells to populate the defect. Accurate membrane adaptation and stabilization, using fixation devices when necessary, are vital.

Minimizing surgical stress and maintaining asepsis throughout the procedure are also crucial. A skilled surgeon’s technique directly correlates with successful bone regeneration and long-term implant stability.

Post-Operative Care and Monitoring

Following GBR surgery, diligent post-operative care is essential for optimal healing. Patients receive detailed instructions regarding oral hygiene, including gentle rinsing and avoiding direct pressure on the surgical site. Soft diet adherence minimizes disruption to the graft and membrane.

Regular follow-up appointments are scheduled to monitor healing progress. Radiographic evaluation, typically via cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), assesses bone formation and membrane integrity.

Early detection of complications, such as membrane exposure or infection, allows for prompt intervention. Patient compliance with instructions and consistent monitoring significantly enhance GBR success rates and long-term stability.

Complications and Management

Potential complications in GBR include membrane exposure, infection, and graft resorption. Prompt identification and appropriate management, like antibiotics or surgical repair, are crucial.

Membrane Exposure

Membrane exposure represents a significant complication in Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR), potentially leading to a compromised healing process and hindering successful bone formation. Exposure can occur due to various factors, including surgical trauma, inadequate soft tissue coverage, or premature loading. When a membrane is exposed, it becomes vulnerable to contamination and can impede the intended exclusion of soft tissues from the bone graft site.

Management strategies depend on the extent and timing of exposure. Early, minor exposures might be managed conservatively with close monitoring and local antimicrobial therapy. However, larger or persistent exposures often necessitate surgical intervention, such as membrane repositioning, primary closure with soft tissue flaps, or even replacement of the exposed membrane. Addressing the underlying cause of the exposure is paramount to prevent recurrence and ensure optimal GBR outcomes.

Infection Control

Maintaining strict infection control is absolutely critical throughout all phases of Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR) to minimize the risk of post-operative complications. Bacterial contamination can severely compromise graft integration and lead to treatment failure. Pre-operative assessment of the patient’s oral hygiene and addressing any existing periodontal disease are essential first steps.

During surgery, meticulous aseptic technique, including sterile instruments, gloves, and drapes, must be employed. Post-operatively, patients should receive detailed instructions on oral hygiene protocols, including gentle brushing and the use of antimicrobial mouth rinses. Prophylactic antibiotics are sometimes prescribed, particularly in cases with increased risk factors. Early detection and prompt treatment of any signs of infection are vital for successful GBR outcomes.

Graft Resorption

Graft resorption, the breakdown and loss of the bone graft material, is a potential complication in Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR). The degree of resorption can vary depending on the type of graft material used – allografts, xenografts, and synthetics exhibit different resorption rates; Early resorption can compromise the stability of the augmented site and hinder successful bone formation.

Factors influencing resorption include surgical technique, vascular supply, and patient-related variables. Minimizing trauma during graft handling and ensuring adequate blood supply are crucial. Careful membrane adaptation and stabilization also help prevent graft displacement and subsequent resorption. Monitoring resorption radiographically post-operatively allows for timely intervention if necessary, potentially requiring further augmentation.

Future Trends in Guided Bone and Tissue Regeneration

Emerging trends include advancements in biomaterials and the integration of growth factors to enhance bone regeneration, promising improved outcomes and predictability.

Biomaterial Advancements

The future of GBR heavily relies on innovative biomaterial development. Researchers are actively exploring novel materials exhibiting enhanced osteoconductive, osteoinductive, and osteogenic properties. This includes modifications to existing materials like titanium and polymers, alongside the creation of entirely new composite structures.

Specifically, focus is shifting towards materials that promote vascularization – crucial for successful bone integration – and deliver sustained growth factor release. Nanomaterials and 3D-printed scaffolds are gaining traction, allowing for customized graft shapes and improved cellular interaction.

Furthermore, “smart” biomaterials responsive to the biological environment are being investigated, offering the potential for self-regulating regeneration processes and minimizing complications. These advancements aim to optimize bone formation and long-term stability.

Growth Factor Integration

Enhancing GBR outcomes increasingly involves incorporating growth factors into the regenerative process. These bioactive molecules, such as Bone Morphogenetic Proteins (BMPs) and Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF), stimulate cellular activity and accelerate bone formation. Delivery methods are evolving beyond simple application, focusing on sustained release systems.

Researchers are exploring incorporating growth factors into biomaterial scaffolds, creating a localized and prolonged stimulus for osteoblast differentiation and angiogenesis. Gene therapy approaches, delivering genes encoding growth factors directly to the defect site, are also under investigation.

Careful consideration is given to dosage and timing, as excessive growth factor concentrations can lead to adverse effects. The goal is to harness their regenerative potential for predictable and efficient bone regeneration.